Replacing Things Lost

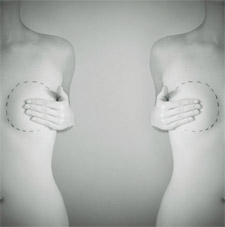

A diagnosis of breast cancer is mind-blowing, and a mastectomy can be devastating. But for some women, reconstructive surgery offers a chance for a silver lining. AMY DEPAUL reports on a troubling question of size. Originially published for The Morning News.

I was still reeling from my breast cancer diagnosis when I began preparing for my mastectomy and reconstruction. I was 45, and only three months earlier I had received a clean bill of health on my annual mammogram, but there was no mistaking the pebble I found under the skin of my left breast. When an ultrasound showed a second tumor in a different part of the breast, I became a clear candidate for mastectomy and eventually, with the discovery of cancer in different locations on the right side, a double mastectomy.

So it was off to the plastic surgeon’s office—not a place I had ever envisioned myself, to be honest. My husband accompanied me for moral support, and we idled in the waiting room and then the exam room; he was reading Breast Cancer Husband while I flipped through a magazine. The doctor walked in, introduced himself and sat down on a stool with wheels that allowed him to scoot around the office at lightning speeds to snatch papers and files as needed. A chatty and energetic sort, he explained early on that no one has to undergo reconstruction, which I appreciated, but that if I wanted to, he would help me determine my options. I told him I was certain I wanted to reconstruct.

He pulled out his pen and opened his file and began asking questions, looking over my medical information: Do you smoke? No. Did they find cancer when you had your cervical cone biopsy? No. “Good,” he said. And then: “What is your current bra and cup size, and what would you like to move up to?”

Huh?

No, I thought. No, he didn’t just imply that I am an obvious candidate for breast augmentation, though some might argue that I was. I looked at my doctor and then my husband, both of whom studiously avoided eye contact with me. In the awkward silence, it occurred to me that my husband might be tempted to weigh in favorably on the augmentation, a move I would have found highly uncool. After all, it’s one thing for a plastic surgeon to point out your supposed anatomical shortcomings, but it’s quite another to hear it from the guy whose laundry you fold and put away. “You better not say anything!” I said to my husband.

I finally managed to stammer a response to the bra inquiry (“It’s 34, um, A”) and said that no, I’d pass on the augmentation. My answer seemed to surprise my doctor (“Oh” was all he could say at first), and then he mentioned that I might want to mull this matter some more and perhaps confer with my husband on the decision. But my mind was pretty much made up that day in the office. The inescapable fact is that I resist any attempts by others to “improve” me. My husband, for the record, never tried to talk me into augmenting. He is a very intelligent man.

Perhaps I wouldn’t have been so taken aback that day if I had known then what I know now, which is that rebuilding a breast or breasts after they have been removed in a mastectomy can allow you options for expansion. Hard to figure—you lose much of the skin and virtually all the internal contents of your breast, and yet you can, in some cases, end up bigger than you started. Increasingly, more women may attempt to do just this, since mastectomy rates are on the rise again, according to a recent study by the Mayo Clinic. But patients should know that reconstruction as it is most typically performed might best be described as medieval. It involves prolonged, torturous skin stretching, and anyone seeking to augment will face an even greater degree of pain and discomfort, something I’ve learned many women are willing to do.

While there are surgical techniques that take a patient’s own fat and muscle from elsewhere on the body, such as the abdomen, to form a new breast, the large majority of cancer patients rebuild using implants. Their reconstruction often begins at the time of the mastectomy; the oncology surgeon removes the nipple and areola, as well as the tissue under the skin. The plastic surgeon then replaces the missing breast tissue with a temporary implant, called a tissue expander, which has a valve that sits under the sewn-up skin. In the months after the surgery, the doctor injects saline into the implant through the valve (think of inflating a tire) to stretch the skin, which makes it grow (think of your abdominal skin during pregnancy, except much tighter). After the stretching is completed, the surgeon replaces the expander implants with final implants or, in the case of removal of only one breast, a single implant, augmenting the other breast to match if necessary.

As it turns out, I’m not the only breast cancer patient who was disconcerted by her plastic surgeon’s focus on size, or, as it is known among the professionals, “volume.” In Pretty Is What Changes, a young woman’s account of getting a prophylactic double mastectomy, author Jessica Queller offers a version of when-cancer-meets-plastic-surgery that makes mine look bush league. She wanted to reduce her breast size to B as part of her reconstruction, which the plastic surgeon vehemently opposed:

“Oh no!” Dr. Ward replied. “You’re an attractive, large-breasted girl—you can’t go with anything smaller than a C.”

“But that’s not what I want,” I replied.

And he even recommended that Queller find a new oncology surgeon—one who didn’t remove so much breast tissue—because leaving some breast tissue behind would have a positive cosmetic effect, despite the detriment of allowing potential cancer to remain in her body. Queller then protests that the point of the surgery is to remove as much breast tissue as possible to reduce the risk of cancer.

The doctor broke into a condescending smile. “So, your risk will be reduced by eighty or eight-five percent instead of ninety. But your new breasts will look fantastic.”

Thankfully, I can say with confidence that my plastic surgeon would never have wanted me to compromise my survival. So at least we were on the same page when it came to that issue. But when it came to augmentation, I’m pretty sure I was out of step with him as well as with the women he reconstructed, judging from his oft-repeated tales of the many patients whom he had stretched to their desired size but who then decided they weren’t ready to quit after all—and who went back for more stretching. No surprise there: I live in the plastic surgery mecca of Orange County, Calif. Still, the rest of the country seems to be following the O.C.’s example; breast augmentation remains the most popular of all cosmetic surgical procedures nationally, up 64 percent in 2007 from 2000, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

I’m guessing that it’s the culture of augmentation that inspires many breast cancer patients’ remarkable commitment to larger breasts in the face of increased pain and suffering. In addition to extreme skin stretching, the pangs of reconstruction (made worse by further stretching to enlarge) include immense pressure on the rib cage, muscle spasms across the chest, restricted arm movement and nerve pain over weeks or months, and sometimes overlapping with chemotherapy. Reconstruction thus revives the eternal question: How much are breasts worth, and how big do you need to be? Consider these excerpts from a discussion on breastcancer.org:

From ‘Traci T’:

…I too am having some pain with my expanders. I’m taking hydrocodone.

I still have 5 more fills to get to where I want to be (a small C) then, he says he has to fill with another 200 cc’s after that to have some skin for nipples. I think. Anyway, I don’t think my skin or ribs can take it. It seems like my mast scar is going to rip open…

One girl here told me that she actually got a broken rib from her expanders!!!!! That freaked me out.

From Traci T again:

Oh yea…I just remembered my doc told me that it’s because the expanders are pressing against them [ribs] and he also told me… no lie… that this process could permanently reshape the shape of your ribs.

From ‘Sociologist’:

I almost passed out yesterday from the pain. One of my male students had to escort me back to my office… I had no idea that the reconstruction would be this uncomfortable.

From ‘Tri’:

I went through the expander/fill process in 2004. It was extremely painful and felt like bricks. I couldn’t lay down the entire process, which meant sleeping sitting upright in a recliner because of the pain and discomfort.

From ‘Jackieb11′:

I have pain in my ribs, under my arm, I have difficulty taking a deep breath and I am doing my best to avoid catching a cold. I was an “A” cup and I want to be a high “C.” I am very small framed and am not sure if that makes it more painful…

And finally, there are some for whom the pain outweighs the gain, such as ‘Kimscharlie’:

I am finally done with the expanders. I ended up at 360cc’s. I don’t know how anyone gets more than that. They started filling me up one week after my surgery. I don’t think I would recommend that. They also tell you to take advil and muscle relaxers… I found only real pain pills work … It was the most uncomfortable time I have had. I, too, started out as a C+ and now will be happy at a B but will probably end up a small B… Just couldn’t do it any more.

Like Kimscharlie, many women choose not to make their reconstruction harder. In Sacramento, Calif., Debra Johnson, the president of the California Society of Plastic Surgeons, finds that her patients are mostly women in their 40s and 50s who aren’t determined to enlarge. Those most likely to change their size have unusually small or else large, drooping breasts, both of which can be difficult to match to a reconstructed breast, which tends to sit higher and look rounder than its native counterpart. In these cases, Johnson adjusts the unafflicted side, either by adding a small implant or lifting or reducing the non-cancerous breast. In cases like mine, in which tissue from both breasts was removed and replaced by expander implants, patients are free to enlarge at will or until the discomfort is too great. Johnson says, “I tell them I will expand you until you say ‘uncle.’”

When it came to the expansion challenge, I threw in the towel as quickly as I could, which meant that I didn’t suffer as long or as acutely as many women. This small blessing I owe at least in part to my husband, whose deferral to me on this issue freed me up to follow my own wishes. Instead of trying to persuade me to augment, my husband left me to make up my own mind. When pressed, he said with characteristic bluntness that large implants would not look right on me. Whether he believed it or not doesn’t matter; I’m just glad he said it, and with conviction. He also agreed with me that basic reconstruction was well worth doing.

By reconstructing, I was able to avoid more severe disfigurement as well as the hassle of double prostheses (or, alternatively, ill-fitting clothes for the rest of my life). My plastic surgeries were underwritten by insurance, in compliance with California laws. Federal legislation has mandated coverage since 1998, and there were 57,102 reconstructions in the U.S. in 2007. (By comparison, there were 347,524 breast augmentations—that is, purely cosmetic, not cancer-related—in 2007.)

Research suggests that breast cancer patients are happy with their reconstructions, despite the fact that cosmetic results are highly variable from patient to patient. One reason might be that reconstruction is the sole positive medical development a mastectomy patient sees amid the pain of losing body parts, fears of metastasis and side effects of chemotherapy.

“These are women who are terrified, and you can provide a positive thing for them to focus on in the face of all the scary stuff,” Johnson says. “I just enjoy these women. I find them very refreshing and happy to be alive.” If, in the process of rebuilding, Johnson can provide a cosmetic boost, she’s all the more happy to do so. “They say, ‘I want a fix. I need a silver lining somewhere.’”

For me, augmentation was not a silver lining for a number of reasons. Foremost, I had never harbored any great yearning to be bigger, and I didn’t want to change my appearance in a way that would draw attention to my cancer. I also don’t like the aesthetic of conspicuous implants—too high, too hard, too desperate-looking. I am thin and small-framed and wanted to remain proportional; oh, and I have an overactive imagination. For me, the prospect of being transformed into a dramatically new self in an operating theater was ghoulish: Frankenstein came to mind. Or worse—Buffalo Bill in Silence of the Lambs as he sits at a sewing machine stitching together human skins.

There were also medical considerations, including thin skin that an implant might wear through in a rare phenomenon called extrusion, vigorous chest muscle spasms, and a delay in wound healing—all practical reasons why I was not ambitious about size. Not that I don’t care how I look.

I still find disfigurement hard, and I feel the loss of my right, normal body every day. I sometimes catch a glance in the mirror after a shower and think sadly, “Really?” At these times, no, I don’t think I look very good, though that is the fault of cancer and not a lack of skill on the part of the plastic surgeon.

I have zipper-like scars across my skin and no nipples, for one thing. (You can get nipples if you want them. It involves carving out flesh from another part of your body and sewing it onto the breast to form the nipple, then tattooing the areola around it. Pass!) But in my clothes, and even in my bathing suit, I look fine. As for size, I think I made the right decision. While even the most understated implants don’t look exactly like the real thing up close—implants can protrude very suddenly and sometimes the skin over them puckers—I’d like to think I appear reasonably normal to the outside world. I’ve learned that looking normal from the outside helps mitigate the distinctly abnormal way I have felt on the inside since I learned I had cancer.

Serious illness and its attendant surgical procedures have spawned all sorts of odd behaviors, such as compulsively checking awfulplasticsurgery.com and watching cheesy medical reality shows. I also have become more vain, developing a minor shopping habit at H&M, and, after being advised by doctors to skip chemotherapy, growing my hair longer than is age-appropriate. I even—very briefly—contemplated wearing makeup. More seriously, I feel an irrational, deeply personal surge of empathy when I see someone in a wheelchair or a burn victim with prominent scars, even though I know I have suffered far less than they.

I am grateful that I don’t have to show my disfigurement to the world, and I often remind myself that reconstruction is less than a sure thing—the process can go wrong and lead to the removal of the implant, which would mean losing the same body part twice. So I’m glad it seems to be working for me, for now at least. But mostly I am grateful to have early-stage cancer and an 89 percent chance that it won’t recur within 10 years, according to my oncologist.

My mother and my aunt have both had cancerous tumors removed from their breasts. Becky, a former neighbor of mine and an exceptionally easygoing mother of three sons, died of breast cancer. She was in her thirties. Rhonda, my older son’s kindergarten teacher, who preferred learning in the outdoors to classrooms, also succumbed to breast cancer. My son is in high school now, but he has not forgotten. How could he? She was the first person he felt close to who died, and I would like to avoid being the second. So you don’t have to remind me that the important thing here is to live. And to live well.

That’s why, when I am tempted to wallow in feeling dissected and disfigured, I look for comfort in odd places. I’m talking, of course, about celebrity culture. Two famous people who illustrate the art of going beyond accepting flaws to embracing them come to mind: One is former New York Giants defensive end Michael Strahan, who refuses to close what some think is an unsightly gap in his front teeth, because, “It’s part of who I am.” The second is actress Emma Thompson, who, when asked in Vanity Fair, “If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?” responded, “Then who would I be?”

Who would I be without my cancer? I’m reluctant to say that cancer has made me a better person. Neither would I call it, as some patients do, “the gift,” for having made me appreciate daily life, though there is some truth to that. Instead, I try to think about cancer as I do about my surgical scars and missing parts and pieces—it is something unfortunate that does not define me but that does, in fact, belong to me. Simply put: I am not my cancer, but it is part of me. While I am glad to have been reconstructed, no procedure can erase or obscure all visible reminders of my affliction, nor what I lived through or might yet face. I wouldn’t want it to.

Our Reviews

Our Reviews